From lions to ghosts, this episode has it all! Host Will Clark and Gavin Whitehead (The Art of Crime Podcast) discuss six noteworthy examples of revolutionary art! You’re in for a treat!

Tennis Court Oath

The Tennis Court Oath by Jacques-Louis David depicts a pivotal moment during the French Revolution in 1789. In this historic event, members of the French Third Estate gathered at a tennis court in Versailles after being locked out of their meeting place. In pledging to remain united until a new constitution was established, the deputies were now revolutionaries. David’s painting captures the solemn determination and unity of purpose among the delegates, although many prominent figures would die in the Terror.

Madame Tussaud’s effigy of the Comte de Lorges

Madame Tussaud, known for her lifelike wax sculptures, created an effigy of the Comte de Lorges during the French Revolution. However, the imprisoned noble never existed.

The Lion of Lucerne

The Lion of Lucerne is a famous monument in Lucerne, Switzerland, designed by Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. Carved into a cliff face, it commemorates Swiss Guards who were killed during the French Revolution in 1792. The sculpture portrays a dying lion resting on a shield bearing the fleur-de-lis of the French monarchy, with a broken spear in its side. It is a poignant symbol of bravery and sacrifice, although controversy has long surrounded the monument.

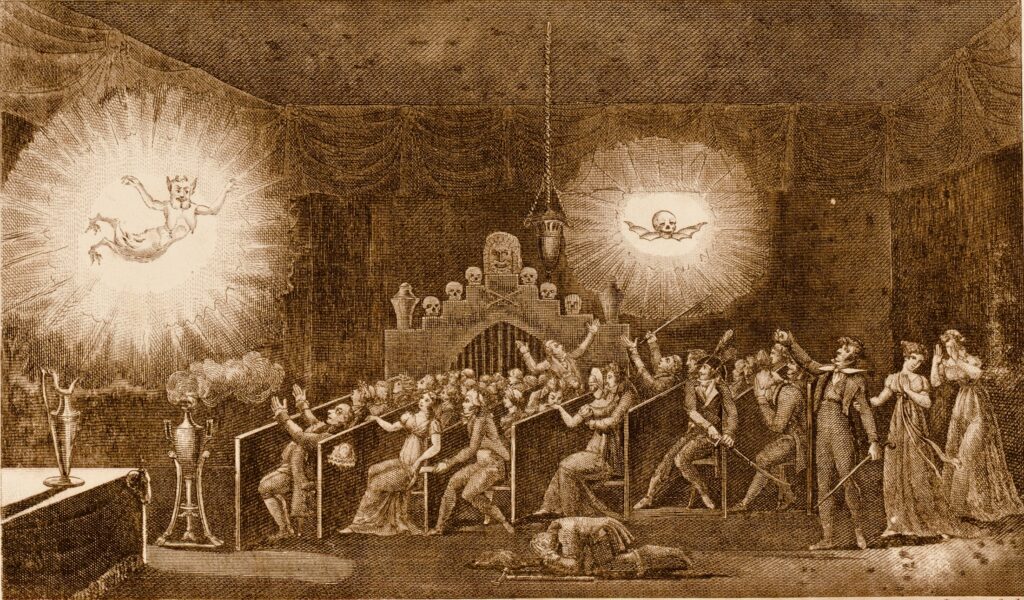

Phantasmagoria

Phantasmagoria refers to a form of entertainment popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, involving magic lanterns to project ghostly images onto screens or smoke. Originating in France, it quickly spread throughout Europe, captivating audiences with its eerie illusions and supernatural themes. Revolutionary figures such as King Louis XI would appear in performances, speaking from the grave!

Vandalism

During the French Revolution, vandalism often took the form of symbolic acts of destruction. People targeted symbols of the Old Regime, such as statues of kings and nobles, religious artifacts, and aristocratic residences, viewing them as embodiments of oppression and inequality. Vandalism served both as a tool for political change and as a potent symbol of the revolution’s transformative aspirations. Its detractors, however, were shocked by the destruction.

Danton’s Death

“Danton’s Death” is a play written by German playwright Georg Büchner in 1835, although it was not performed until much later due to its controversial themes. The play dramatizes the final days of Georges Danton, a prominent figure of the French Revolution, and his conflict with Maximilien Robespierre. It explores themes of power, idealism, and betrayal, portraying Danton as a charismatic leader grappling with the consequences of revolutionary violence and his own moral compromises. Büchner’s work delves into the complexities of revolutionary fervor and the tragic personal and political conflicts that ultimately lead to Danton’s downfall and execution during the Reign of Terror.